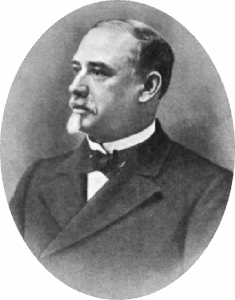

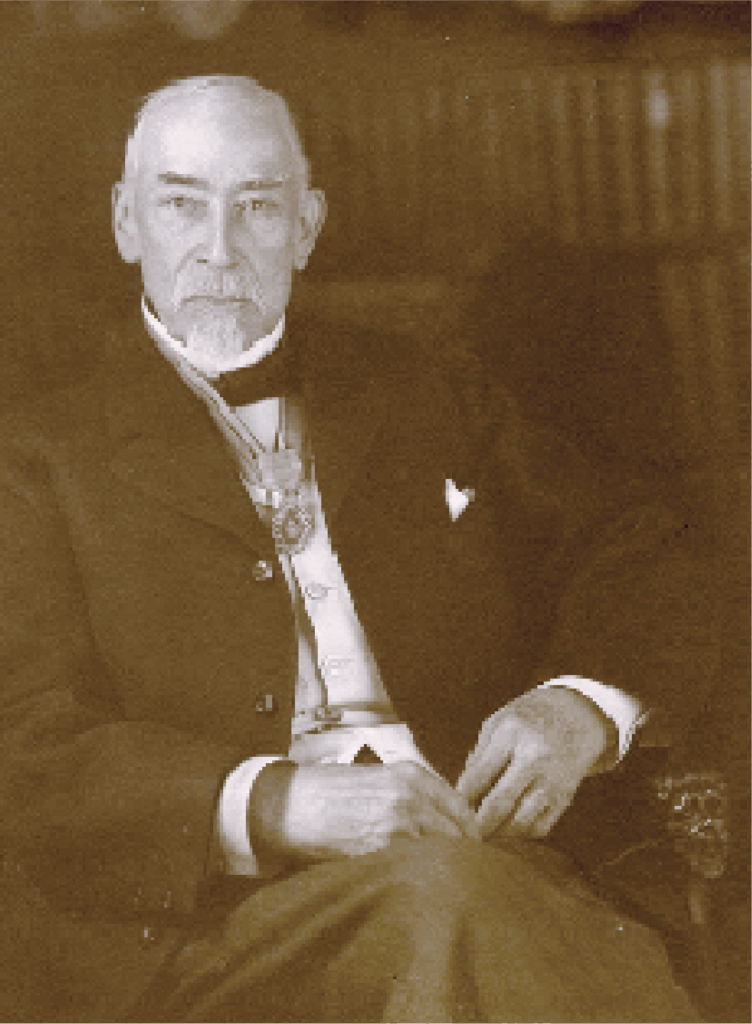

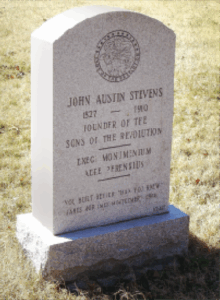

Our Regards to John Austin Stevens, Jr.

Founder of the Sons of the Revolution

By Mark Jakobowski, General President

& David W. Swafford, Editor

As we approach the 250th anniversary of the United States and kick off fundraising efforts for our “250 for 250” project, it is an appropriate time to doff our collective hat to the memory of John Austin Stevens, Jr.

Stevens, as many know, founded the Sons of the Revolution in his hometown of New York City in late 1875. That same year Congress passed the first Civil Rights Act and baseball’s National League was formed. Ulysses S. Grant was wrapping up his second term as President and considering a third.

Born in New York City to John Austin Stevens, Sr., and Abigail Perkins Weld, on January 21, 1827, Stevens was in his late forties when he organized the Sons. Like any other endeavor this man pursued, he founded the Sons with earnest and forthright zeal, characteristic rectitude, and pointed focus. These traits come to light through the surviving records of the organizations to which he belonged—as well as from what observers of his day noted, and from his own private and published writings.

All these accounts reveal Stevens as a consummate do-er. He was a merchant, public speaker, gifted writer, magazine publisher, scholar, researcher, and elected board member of the New York Chamber of Commerce, the New York Historical Society, and other associations.

By all indications, he was a man of substantial energy who led a life of considerable word and deed, much of it in the company of renowned individuals.

Proud of his Grandfather

Although Stevens was naturally influenced by his father and his father’s circle of friends and associates, as a young man he grew increasingly enamored by his grandfather’s place in American history.

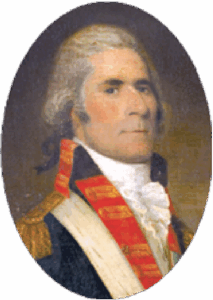

Ebenezer Stevens II died in 1823, four years before John Austin, Jr., was born. The latter grew up in the shadows of the former, perhaps learning all about his legacy even from an early age. His grandfather participated in the Boston Tea Party and became an officer of artillery in the Continental Army, assigned first under Henry Knox and later under Lafayette.

He guarded the Boston Neck during the months of siege after the Battle of Bunker Hill and saw combat action at Ticonderoga, Saratoga, and Yorktown. He was breveted to lieutenant colonel on April 30, 1778 and to colonel by the end of the war. During the course of the Revolution, Stevens gained a respectable reputation and was often in the company of men like Knox, Arnold, Schuyler, Lamb, and Lafayette. Washington was well aware of his worth to the army.

He guarded the Boston Neck during the months of siege after the Battle of Bunker Hill and saw combat action at Ticonderoga, Saratoga, and Yorktown. He was breveted to lieutenant colonel on April 30, 1778 and to colonel by the end of the war. During the course of the Revolution, Stevens gained a respectable reputation and was often in the company of men like Knox, Arnold, Schuyler, Lamb, and Lafayette. Washington was well aware of his worth to the army.

On November 25, 1783, Evacuation Day in New York City, he escorted Washing- ton into the city during the latter’s triumphal entry. Stevens was one of the founders of the Society of the Cincinnati and in time held the office of Vice President of the New York branch.

In 1799, sixteen years after Washington’s farewell to his officers at the Fraunces Tavern, Stevens served as one of eight military pallbearers from the Cincinnati to escort Washington’s funeral urn through the streets of lower Manhattan.

After the Revolution, he resigned his commission in the Continental Army but joined the New York militia. Gov. John Jay appointed him as a brigadier general and tasked him with improving the defenses around New York City. Among the improvements was a rather large fortress situated at Hallett’s Point on the East River, Queens County, which was named in the Stevens’ honor. Prior to the conclusion of the War of 1812, he mobilized militiamen to defend New York City in case of a British attack.

After that war was concluded, Ebenezer retired from the militia and established himself as a city merchant. He became quite successful importing European wines and spirits, operating out of 222 Front Street in Manhattan. He berthed an impressive fleet of “new and fast” ships along nearby South Street.

Lighting the Fire

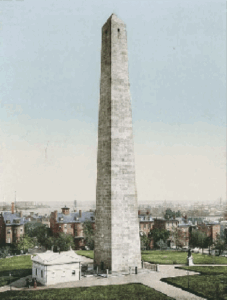

In Stevens’ inaugural year at Harvard, 1842, when he was 15 years old, he accompanied his class to hear U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster speak at the site of the Battle of Bunker Hill. The occasion marked the laying of the cornerstone of the obelisk monument there to perpetuate the memory of the fallen.

Hearing Webster’s speech was a life-defining moment for Stevens. Measuring 10,000 words, the discourse so moved him that it engendered in him a lifelong belief that all red-blooded and blue-blooded Americans should honor their patriot ancestors. A fragment of the Secretary’s words follow:

“Our object is, by this edifice, to show our own deep sense of the value and importance of the achievements of our ancestors,” Webster said, “and by presenting this work of gratitude to the eye, to keep alive similar sentiments, and to foster a constant regard for the principles of the Revolution.

“Human beings are composed not of reason only, but of imagination also, and sentiment; and that is neither wasted nor misapplied which is appropriated to the purpose of giving right direction to sentiments and opening proper springs of feeling in the heart.”

Thirty-five years later, by the time Stevens was 50, it was his turn to speak before the public on hallowed grounds. The occasion was the centennial celebration of the Battle of Freeman’s Farm, held Sept. 19, 1877. In contrast to Webster’s speech, Stevens’ discourse on Burgoyne’s campaign tallied 16,000 words.

“Proud to be chosen to recite the incidents of the campaign which culminated in the surrender of the first British army to the infant republic,” he began, “it is a source of still greater pride to me that… my grandfather, Col. Ebenezer Stevens, of the Continental army, who, on this field, a century ago, directed, as Major Commandant of the Artillery of the Northern Department, the operations of that arm of the service which in great measure contributed to and secured the final success of the American troops…”

“Proud to be chosen to recite the incidents of the campaign which culminated in the surrender of the first British army to the infant republic,” he began, “it is a source of still greater pride to me that… my grandfather, Col. Ebenezer Stevens, of the Continental army, who, on this field, a century ago, directed, as Major Commandant of the Artillery of the Northern Department, the operations of that arm of the service which in great measure contributed to and secured the final success of the American troops…”

Stevens concluded his speech by saying, “The last days of a century are closing upon these memorable scenes. How long will it be ere the government of this Empire State shall erect a monument to the gallant men who fought and fell upon these fields and here secured her liberty and renown?”

Guided by the Era

As all persons are, Stevens was a product of the times he lived in, the place he lived in, and the family into which he was born. By 1840, his father was a co-founder and president of the largest bank in the country, the Bank of Commerce in New York. He was also president of the Merchant’s Exchange. Through his father, Stevens met many influential persons from New York, Philadelphia and Washington.

Both Stevenses belonged to the New York Chamber of Commerce. By the 1850s, a plank which they both actively supported and promoted through the Chamber was free trade, because it was good for commerce and banking and, thereby, in their train of thought, good for the nation.

As the country entered the 1860s, Stevens, Jr., was elected Secretary of the Chamber, a position which his father had held years before. He himself would hold the office for six years, 1862 to 1868. During that time, he was closely involved with raising money (shareholders) for a variety of national and international projects of interest to the business community.

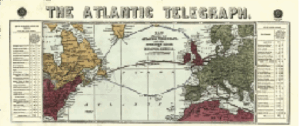

One of those projects was the laying of a second telegraphic cable between North America and Europe, after the first cable failed. Repeated attempts were necessary, but success finally came in 1866. Throughout that period, Stevens was in frequent touch with wealthy industrialists and merchants such as Cyrus Field, Peter Cooper, William E. Dodge, and Abiel Abbot Low.

One of those projects was the laying of a second telegraphic cable between North America and Europe, after the first cable failed. Repeated attempts were necessary, but success finally came in 1866. Throughout that period, Stevens was in frequent touch with wealthy industrialists and merchants such as Cyrus Field, Peter Cooper, William E. Dodge, and Abiel Abbot Low.

During the Civil War, Stevens and his father were in regular contact with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase and even President Lincoln himself. In 1861, after the Battle of Bull Run, Chase went to New York to seek advice from bankers about averting a financial crisis. The government was essentially insolvent and could not prosecute a war effort. Dozens of bankers in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia formed an association to keep the government afloat—at least until the following year.

Stevens, Sr., as head of the largest bank, was named chair of the group and orchestrated a loan of $150 million in three tranches. He also committed $50,000 of his personal funds to the venture, which today would equal over $1.8 million.

“The bankers realized that without a firm government, their own operations were imperiled,” wrote historian Louise Phelps Kellogg. “(A)t the time of the operation, the transactions were of daring boldness.”

Stevens, Jr., was in lock-step with his father, in terms of supporting the Union government. In his own right, he played a central role in helping organize and promote the Mass Meeting of Loyal Citizens held on Union Square in July of 1862. By the next year, he was directing the Loyal Publication Society of New York, which critics called a propagandist operation. The Society ultimately published ninety pro-Union pamphlets, each one with a printing of 100,000 copies.

In 1864, the year the Bank of Commerce was designated a national bank, the elder Stevens was seventy years old. In two more years, he would step down as bank president. The younger Stevens maintained his involvement as Chamber Secretary and, during Lincoln’s presidency, assisted the Chief Executive by helping organize logistics and helping assemble expeditions for the Union Army.

Not long after the conclusion of the war, he visited Lincoln to urge him to name a day of national rejoicing over the end of the war. The very next evening, Lincoln was mortally wounded by an assassin’s bullet.

Building a Monument

When Stevens stepped down from his role as Chamber Secretary, three years had passed since the war’s conclusion and two years since his father’s retirement as bank president. In his later years, John Austin Stevens, Jr., devoted his life to his favorite activities: researching and writing about American history.

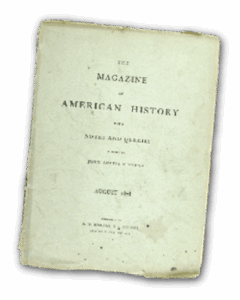

From 1877 to 1893, he published a magazine simply named “Magazine of American history.” In 1882, he assisted in writing the Reminiscences of Gen’l Samuel B. Webb of the Revolutionary Army, published by Higginson Book Co.

By 1898, his biography of Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin (who served three terms, 1801-1814) was published by Houghton, Mifflin and Co. and became part of the publisher’s American Statesmen Series. In the same year, he also penned “A Memoir of William Kelby, Librarian of the New York Historical Society.”

For as personally fulfilling as all of that was, nevertheless, his literary endeavors did not completely quench his patriotic calling. He needed to do something greater, something that would involve his fellows in memorializing the generation of patriots who gave their all so that American liberty and independence could be achieved.

His quest was answered by organizing the Sons of the Revolution, something much larger than himself. Even in that, he took after his grandfather’s example. Ebenezer had not only co-founded the Cincinnati, but also the Tammany Society and Society of New England.

It has been said of Stevens, Jr., that he founded the Sons because he did not qualify for membership in the Cincinnati. Such a simplistic statement, while partially true, belittles his more altruistic motivations. Although he was admittedly disappointed, the decision with his good friends William Kelby and Asa Bird Gardiner to organize the Sons was for the greater public good.

It has been said of Stevens, Jr., that he founded the Sons because he did not qualify for membership in the Cincinnati. Such a simplistic statement, while partially true, belittles his more altruistic motivations. Although he was admittedly disappointed, the decision with his good friends William Kelby and Asa Bird Gardiner to organize the Sons was for the greater public good.

This Society expanded the breadth and scope of patriotic societies by creating more opportunities for membership and fraternal camaraderie. The Sons welcomed descendants of officers, ensigns, militia or ship mates, all who risked their lives or limbs in battle for the Cause.

Hamilton Fish, the long-tenured President of the New York State Society of the Cincinnati, welcomed the Sons of the Revolution and formed a congenial relationship with the new organization, calling it “the little Cincinnati.”

The biggest difference between the two, to this day, is the membership requirements. If a man’s patriot-ancestor (male or female) took up a rifle, musket or cannon during the war, or served in a patriot-minded legislature, or signed one of the great founding documents of this country, that action qualifies him, the descendant, for membership in the Sons—as long as the genealogical ties are proven.

The biggest difference between the two, to this day, is the membership requirements. If a man’s patriot-ancestor (male or female) took up a rifle, musket or cannon during the war, or served in a patriot-minded legislature, or signed one of the great founding documents of this country, that action qualifies him, the descendant, for membership in the Sons—as long as the genealogical ties are proven.

By 1883, to mark the centennial anniversary of Washington’s farewell to his officers, Stevens was tapped by the mayor of New York to organize official, civic festivities for the occasion. He was most concerned with planning the Turtle Feast, held at Fraunces Tavern. On December 4 of that year, in the Long Room, as Samuel Fraunces served the dinner, Stevens rose and proposed the first toast of the evening to George Washington.

A report in Leslie’s Newspaper stated, “When Mr. John Austin Stevens arose to give the first toast, ‘George Washington,’ the whole assembly rose, with Tobys held aloft, and gave three rousing cheers, while a Continental drummer and fifer marched in, playing with splendid dash the saucy, stirring air of ‘Yankee Doodle.’

A report in Leslie’s Newspaper stated, “When Mr. John Austin Stevens arose to give the first toast, ‘George Washington,’ the whole assembly rose, with Tobys held aloft, and gave three rousing cheers, while a Continental drummer and fifer marched in, playing with splendid dash the saucy, stirring air of ‘Yankee Doodle.’

“‘Who was Washington?’ called out the toastmaster.

“‘First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen!” ran the reply, shouted out in a thunderous chorus that rattled the narrow windows and made the crisp holly-leaves and flaming berries dance on the wall.”

On that same occasion, the New York Society was officially re-chartered, with a new constitution, and Stevens was elected its President. He stood down the following year.

Six years afterward, the General Society was organized. Structured along the same lines as the Cincinnati, the first State Societies to come under its confederation were New York, Pennsylvania and the District of Columbia.

In 1898, SRNY President Frederick Tallmadge presented Stevens with the Society’s Founder badge and wrote to him:

“[T]he noblest tribute that can be paid to your energy and your patriotism is the fact that this Society, organized by you, now numbers over two thousand members. That of itself is the proudest monument you could ask for to your energy and patriotism.”

John Austin Stevens, Jr., passed away at his Rhode Island home in 1910. A funeral procession was arranged in New York where thousands gathered along the procession route and saw the Fraunces Tavern draped in black, the universal sign of mourning.